#charles x

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

the grandchildren of louis XV through his son, the dauphin

#historyedit#perioddramaedit#18th century#19th century#louis xvi#louis xviii#charles x#madame elisabeth#madame clotilde#ngl i did sob a little bit making these#there's just something heartbreaking about artois and provence ending up where they ended up because who would have thought?#mine#*

180 notes

·

View notes

Text

A set of porcelain dishes with images of the French Royal family on it, made in 1778-1779.

The coffee pot has an image of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette.

The milk jug shows the Comte and Comtesse de Provence.

The sugar pot depicts the Comte and Comtesse d'Artois.

The cups portray 3 princesses: Madame Louise, Madame Clotilde, and Madame Elisabeth.

Source

#marie antoinette#louis xvi#comtesse d'artois#charles x#louis xviii#madame louise#madame clotilde#madame elisabeth#chateau de versailles#marie josephine of savoy#maria theresa of savoy#long live the queue

126 notes

·

View notes

Text

Post on a Short Period Concerning Political Spectrums from 1789 to 1848 to Counter Misconceptions About the Far Left and Far Right

Sociétés des Jacobins (Jacobin Societies)

We all know the famous phrase: “The far right and the far left are the same thing; they’re no better, etc.” However, the far right and the far left are clearly not the same. This definition should not be taken literally, as it pertains more to the Restoration period concerning property rights (and even then, it’s more complex). The far right believes that property should belong to the traditional elites (the emigrated nobility), while the far left has a different view like sharing the property for maximum people . And first, on which political spectrum are we basing this? From which period?

In 1789, those considered far left were deputies like Pétion, François Buzot, and Maximilien Robespierre. Non-deputies aligned with the far left included figures like Danton, Camille Desmoulins, and Manon Roland, among many others.

However, during the second revolution in 1792, these figures would split. What came to be known as the Girondins (though there were many differences within this group) would constitute the more conservative wing (including Buzot, Pétion, and Manon Roland), while the Montagnards represented the far left. Yet, on the issue of slavery, many from both sides agreed on its abolition: Brissot proposed a gradual abolition, Sonthonax was sent to Saint-Domingue to enforce it, and Abbé Raynal (though seemingly conservative on property rights) was highly reformist on slavery, even calling Toussaint Louverture the “Black Spartacus.” The Montagnards, like Danton and Jean-Paul Marat (who supported the Haitian revolt and predicted its independence), joined in this cause, as did the Hébertists like Pierre Gaspard Chaumette, who shared Marat's views on Haiti.

The first major division between the Girondins and the Montagnards was over the issue of war, and it’s clear that the Montagnards were ultimately proven right on these question. What we now call the far left of this period consisted of elements considered a faction called the Hébertists (including individuals like Momoro, Chaumette, Hébert, François Hanriot, Charles Philippe Ronsin, Vincent François Nicolas, etc.) and another group known as the Enragés (Jacques Roux, Théophile Leclerc, Jean-François Varlet, Pauline Léon, Claire Lacombe, etc.). These two factions were also called ultra-revolutionaries and were much more socially engaged on certain political issues than Montagnards like Robespierre, Desmoulins, Danton, etc.

During the insurrection from May 31, 1793, to June 2, 1793, in which the Paris Commune, led in part by François Hanriot (following the arrest of Hébert and the Sans-Culotte delegation demanding his release, along with Isnard’s speech and the Commission of Twelve), expelled 21 Girondins who were initially placed under house arrest (we all know what happened next, but that’s not the focus here). The Montagnards who approved this insurrection portrayed themselves as allies of the Sans-Culottes. However, it’s important to note that not many of them viewed this leftist faction favorably (Marat became an opponent of Jacques Roux, and after his death, his widow Simone Evrard gave a speech against Jacques Roux and Théophile Leclerc among others ). The Committee of Public Safety and the Convention illegally persecuted Jacques Roux to the point where he committed suicide, suggesting that the Montagnards were beginning to shift further to the right. Furthermore, there were internal conflicts within the far left. The Hébertists clashed with the Enragés and later took up their petitions after many of them were removed from the political scene.

Later, on September 5, 1793, as the French Revolution seemed more endangered than ever, the Commune, led by figures like Chaumette, Hanriot, and Pache, arrived at the Convention without opposition, securing concessions such as the maximum price controls and the raising of a revolutionary army. The Montagnards seemed ready once again to support this far left on some points. However, conflicts and internal struggles soon reemerged. This time, the Indulgents, including Camille Desmoulins, Georges Jacques Danton, and Pierre Philippeaux, formed the Montagnards’ right wing. Initially, the majority of the Convention supported them against the elements considered far left (notably Robespierre, among others), but the majority of the Committee of Public Safety eventually realized they had also underestimated the Indulgents and opted for a middle-ground policy. The struggles among these different factions further weakened the Montagnards. However, they all shared a common goal of celebrating the abolition of slavery. This wasn’t enough for reconciliation; most far-left elements (Pache and Hanriot were notably spared from the Hébertist arrests) were politically eliminated (and it’s important to note that Billaud-Varenne and Collot d’Herbois, who represented the far left of the Committee of Public Safety, participated in this elimination).

Regarding property rights, the entire political class was very timid, even the Enragés and Hébertists, who were more focused on economic issues like taxation. However, some like Momoro apparently began to consider land redistribution like sharing large farms, but without a clear plan (and far from any notion of collectivization of agriculture) . There was a concession made by the Convention on property rights with the Ventôse Laws, perhaps? Previously, when the property of someone convicted of being an enemy of the Republic was seized, it went directly to the state. With these laws, the property was supposed to be redistributed to the needy, perhaps even the property left by émigrés. This was rarely, if ever, implemented.

Later, the eliminations continued with the Indulgents, internal struggles persisted in Thermidor, and the left suffered its final blow following the repression of May 20, 1795.

Indeed, even before May 20, 1795, there was a rightward turn at the end of 1794. In 1795, economic liberalism exacerbated the situation of the popular classes, leading to the insurrection of 1st Prairial Year III. The repression provided an opportunity for the right to eliminate from the political scene people like Goujon and Charles Gilbert Romme, who were considered the last Montagnards.

During the Directory, new far-left elements emerged, the most well-known being the Babouvists. Gracchus Babeuf’s “Manifesto of the Equals” was seen as promoting equality. Nevertheless, while some consider Babeuf to be a precursor to communism and he did advocate for deep social change, his interest was limited to agricultural domains. Lazare Carnot, who led the repression of the Babouvists, was seen as belonging to the right political wing .

The most interesting case considered far left is the neo-Jacobin Bernard Metge. In his work “Dialogue between a Representative of the People and a Former Administrator,” he sharply criticizes the Council of Five Hundred for ignoring the opinions of citizens, yet he also delivers a violent critique of the Babouvists, arguing that their ideology would, in his own words, produce nothing but lazy people. He wrote to the Minister of Police from prison, where he was detained, saying, “Indeed, preach the sharing and equality of goods, and you will have lazy people.” Although a fierce opponent of Sieyès, he advocated political liberalism and supported the Constitution of Year III. However, in his writing that sealed his fate, “The Turk and the French Soldier,” we see another side of Metge: he could be interpreted as opposing expansionist and conquest wars, notably by defending the Egyptians, but also as glorifying the right to resist. He also glorifies Brutus.

When he was arrested and executed by the Bonaparte regime (then the First Consul) for his opinions, he was considered one of the 34 anarchist leaders by the Brumaire regime. On this political spectrum, he was seen as a far-left figure, while on another spectrum, like in 1794 or around 1848, he would likely have been considered a right-wing figure. Metge was executed in a parody of justice. For more details on this revolutionary, visit this Tumblr post: https://www.tumblr.com/nesiacha/756533326215528448/the-jacobins-executed-by-bonaparte.

The most interesting example from this period is Lazare Carnot. Initially a Montagnard in 1793 when he was on the Committee of Public Safety, during the Directory, he took an increasingly right-wing position, including the repression of the Babouvists, where even Barras hesitated. He was certainly the Minister of War under Bonaparte, but in a sense, he found himself once again on the far left of the political spectrum under Bonaparte’s Consulate (a deliberate provocation on my part to better highlight the complexity of different periods on the political spectrum) because he was in the official opposition (after all, the rest of the opposition was either silenced, imprisoned, or deported, like Félix Lepeletier, etc.). He was marginalized for opposing the creation of the Empire.

Then we have the case of the Restoration with the “Chambre introuvable” appointed by Louis XVIII, long considered a chamber more royalist than the King (including figures like Louis de Bonald). Some analyses tend to moderate this; while it’s true there were émigrés from the nobility, the bourgeoisie aspiring to be ennobled, turncoats, and provincial notables, it’s also true that ultra-royalists like Charles X influenced it, making it far more right-wing politically than any other period. Decazes and, more importantly, François Guizot stood up to the ultra-royalists and advised dissolving the Chamber.

Chambre introuvable

Constitutionalists (39) Color to the left Ultraroyalists (350) Even if we have to give more thought to the ultra-royalist side

Yet, under Louis Philippe I’s political spectrum, Guizot was one of the most conservative figures. He was the staunchest defender of conservative and right-wing policies.

François Guizot (1787-1874) painted by Jean-Georges Vibert after a portrait by Paul Delaroche.

Through all these examples, I wanted to caution against the misconception that far left equals far right. History has shown the opposite through the examples cited above, demonstrating that the economic or property-related views of the far left and far right are not the same at all. Individuals situated on the far left can shift to the most conservative right-wing positions depending on the political spectrum of the period, and vice versa, without necessarily changing their political ideas.

Sources:

Antoine Resche

Jean Marc Schiappa

Jean Clément Martin

Bernard Gainot

#frev#french revolution#napoleonic era#louis xviii#Charles X#Monarchy#political spectrum#convention#constitutional monarchy

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

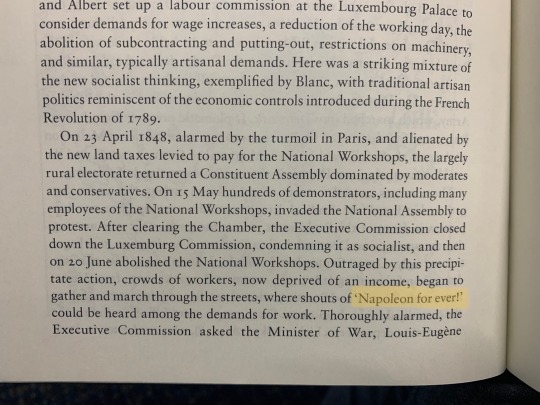

Napoleon as a rallying cry during the revolutions in France during the 19th century

July Revolution (French Revolution of 1830):

French Revolution of 1848:

Source: The Pursuit of Power: Europe 1815-1914, Richard J. Evans

#The Pursuit of Power#Richard J. Evans#Evans#Napoleon#napoleon bonaparte#Talleyrand#Charles X#Thiers#Marmont#Lafitte#Jacques Lafitte#Louis-Philippe#Lafayette#Revolution#french revolution#July Revolution#1848 revolutions#Revolution of 1848#1848#napoleonic era#Blanc#first french empire#napoleonic#history#french history#my pics#book#book quotes#revolution of 1830#France

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

Charles X (1757–1836), King of France, after Gérard

Artist: Henry Bone (British, 1755-1834)

Date: 1829

Medium: Enamel

Collection: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, NY, United States

Charles X, King of France

Charles X (Charles Philippe; 9 October 1757 – 6 November 1836) was King of France from 16 September 1824 until 2 August 1830. An uncle of the uncrowned Louis XVII and younger brother of reigning kings Louis XVI and Louis XVIII, he supported the latter in exile. After the Bourbon Restoration in 1814, Charles (as heir-presumptive) became the leader of the ultra-royalists, a radical monarchist faction within the French court that affirmed absolute monarchy by divine right and opposed the constitutional monarchy concessions towards liberals and the guarantees of civil liberties granted by the Charter of 1814. Charles gained influence within the French court after the assassination of his son Charles Ferdinand, Duke of Berry, in 1820 and succeeded his brother Louis XVIII in 1824.

#portrait#charles x#king#french king#standing#royal robes#indoors#classic architecture#full length#drapes#hat#table#cushion#british art#european art#french culture#french monarchy#french history#19th century painting#enamel

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

CHARLES X OF FRANCE

CHARLES X OF FRANCE

9 October 1757 – 6 November 1836

King Charles X of France was the younger brother of Louis XVI. He was born at the Palace of Versailles, whilst his grandfather was king. His brother Louis married Marie Antoinette and later became king.

In 1773, Charles married Marie Therese and had five children. Charles was considered the most attractive member of his family, his wife Marie was considered ugly, and she was known for having many affairs. Charles was on good terms with Louis and Marie Antoinette. After the storming of the Bastille, Charles, his wife and children left France and fled to Savoy, where his wife was born. His brother Louis and Marie Antoinette were both executed during the French Revolution in 1793. Louis’s son and heir was tortured and died of neglect. Charles moved to England, where George III looked after him. Charles’ older brother Louis XVIII was named king of France. Charles’s son Louis Antoine married Marie Therese in 1799, she was the daughter of his brother and Marie Antoinette.

Louis XVIII moved to England and was now in a wheelchair. The Allies captured Paris a week after Napoleon abdicated and Louis XVIII was restored as king. Louis Antoine and Marie Therese returned to France and stayed in the Tuileries Palace, on arrival Marie Therese fainted because that is where she and her family where imprisoned before her family were killed, she was the only survivor. Louis XVIII died in 1824, and Charles X became king. He ruled for 6 years from 1824 – 1830 until the July Revolution of 1830, which resulted in his abdication in favour of his grandson Henry. Charles went into exile to England and then to Austria.

Charles died in Gorizia, in the Austrian Empire. He was the last of the French rulers from the House of Bourbon who were descended from King Henry IV.

#CharlesX #CharlesXofFrance #LouisXVI #marieantoinette #frenchrevolution #napoleon

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Richard III and The July Revolution

When I finally saw the Ian McKellan Richard III film I was a bit disappointed, his performance was great and there were interesting ideas to come from the concept of adapting this play to the 1930s. But those ideas weren’t explored fully and the other performances were kinda dull.

But my biggest pet peeve was removing Margaret of Anjou, now her presence in this play is it’s most explicit historical inaccuracy, the historical Margaret was not in England anymore during any of this time period, but an adaptation that removes it from even the pretense of being about actual history doesn’t need to worry about that. As a story, her functioning as a Prophetess of Doom is a lot of why this play works and is why I’m glad the first version of it I ever watched was The Hollow Crown series where she’s played by Sophi Okonedo.

Thinking about the idea of adapting this play to other time periods got me to thinking as a part-time Francophile about the idea of using it as a framing device for a fictionalization of the July Revolution of 1830.

Charles X of France and this popular view of Richard III have in common being the youngest of three brothers who was more of a blatant tyrant then his older brothers and the end of his Dynasty overthrown in a Revolution that could also be viewed as more of a Coup.

Charles was also rumored to have had an extramarital affair with Marie Antionette. Meanwhile he never married a daughter of Marie Antionette but his son did.

Orleans would thus fill the role of Richmond and everyone’s favorite crossover plot-line between the American and French Revolution the Marquis de Lafayette can fill the role of Lord Stanley crowning the new King at the end.

But here’s where specifically my Shadowmen interests come into play. The quasi Prophetess role of Margaret of Anjou can be filled by Josephine Balsamo the Countess of Cagliostro. As a daughter of Josephine she too has a connection to a recently overthrown dynasty.

#Josephine Balsamo#Countess Cagliostro#Margaret of Anjou#Richard III#July Revolution#July Monarchy#Charles X#Francophile#Olreanist#Marie Antionette

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

My incredible drawing of "the Virgin Mary holding baby Polignac and her AK47"

this is a private joke about french politician Jules de Polignac ignoring the literal french revolution in Paris's streets back in 1830, and saying to king Charles Xth "the virgin mary told me not to worry", which became a running gag. and don't worry to much about the ak47. with @justanothergaynerd <3

#artists on tumblr#art#drawing#illustration#doodles#sketches#my art#charles x#polignac#history#historical memes#historical meme

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Louis Philippe I vs Charles X (It's King vs King.) During the July Revolution.

This is a revolution between Kings. First one is Louis Philippe I, and the Second one i is Charles X. The fight between the Kings of France.

#kingdom of france#July Revolution#July monarchy#Bourbon restoration#Charles X#Louis Philippe I#Revolutions of 1830#History#Historical#King#Kings

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

#delusional til i die#x reader#star wars x reader#anakin skywalker x reader#anakin skywalker#tom riddle#slytherin boys x reader#formula 1#f1 x reader#leon kennedy x reader#the vampire diaries#the originals#max verstappen x reader#spencer reid x reader#klaus mikaelson x reader#genshin impact#genshin impact x reader#harry potter#harry potter x reader#fanfic#fan fiction#charles leclerc#lando norris#kpop#dean winchester x reader#sam winchester x reader#anime#naruto#gojo satoru x reader#jujutsu kaisen

77K notes

·

View notes

Text

Bee Movie (2007) dir. Simon J. Smith & Steve Hickner X-Men: First Class (2011) dir. Matthew Vaughn

#bee movie#x men first class#xmenedit#beemovieedit#jerry seinfeld#charles xavier#erik lehnsherr#marveledit#filmedit#filmgifs#doyouevenfilm#fyeahmovies#moviegifs#cinemapix#dailyflicks#chewieblog#userelysia#userrobin#userrlaura#usergal#userel#mikaeled#useraurore#userallisyn#userfilm#usersugar#userclayy#kane52630#gifs#movie

43K notes

·

View notes

Text

I commend to God my wife and my children, my sister, my aunts, my brothers, and all those who are attached to me by ties of blood, or by any other manner whatsoever. I pray God especially to cast the eyes of his mercy on my wife, my children, and my sister, who have suffered so long with me; to support them by his grace if they lose me, and for as long as they remain in this perishable world.

#louis xvi#marie antoinette#marie therese charlotte#louis xvii#madame elisabeth#madame victoire#madame adelaide#louis xviii#charles x#house of bourbon#french monarchy#long live the queue

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

I never understood the term "reign" of terror . I mean Louis XVI reigned as king, Napoleon reigned as emperor (I would rather think of a term which is closer to military dictatorship, I also contest the term which qualified Napoleon as a "despot enlightened" but that's another story…), Louis XVIII, Charles X reigned as kings. In the case of the French revolutionaries in this period mentioned, these deputies are people elected by universal suffrage and there is no absolute power. In fact there is not a single deputy who could have absolute power. For example the Committee of Public Safety is subject to the Convention which decides by a majority vote whether it can be renewed or not.Laws must be passed by a majority of the Convention, etc... So there is not a reign of deputies. Even the historian Patrice Gueniffey, who is clearly not a supporter of revolutionaries from the Mountain, contests this story of absolute power.

I will one day do a more detailed post on this period on what I think of it...

#french revolution#Louis XVI#Louis XVIII#Charles X#Historian#history#Napoleon#reign of terror#Terror

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

magneto: how do you have so much faith in humans to do the right thing when they have proven you wrong time and time again?

the humble charles xavier:

23K notes

·

View notes

Text

Portrait of Charles X

Artist: Horace Vernet (French, 1789–1863)

Charles X King of France

Charles X (Charles Philippe; 9 October 1757 – 6 November 1836) was King of France from 16 September 1824 until 2 August 1830. An uncle of the uncrowned Louis XVII and younger brother of reigning kings Louis XVI and Louis XVIII, he supported the latter in exile.

#portrait#charles x#french monarch#french#european#Horace vernet#french painter#man#uniform#king#french royalty6

2 notes

·

View notes